- Lightplay

- Posts

- In the Night Kitchen

In the Night Kitchen

a classic children's book about being baked into a cake • plus: treating AI as the adversary, three plinths in the desert, “The Hand,” a struggling prop house, + SPICE

Dear Reader,

This Wednesday, for the first time in a month, I remembered my dreams. I didn’t write them down, because I knew I would remember them: heavy trains on old train tracks, precarious above the sea. They were intense, even scary, but I was glad to have them. I hadn’t remembered a single dream in over a month.

The last month was a busy time for me. Work, family, and travel took all my time and then some. I kept wanting to write here, but as with dreams, there wasn’t space for it. And maybe other people can force it, but for me, I have to actually make space to write. Just like if I want to dream, I have to go to bed early enough for a full night’s sleep.

I say this to record that I am coming back into myself, and back into my art. I’m excited to be back here, in your inbox, with another Lightplay. I hope you will find it worth the wait.

– Jasper

You’re receiving this edition of Lightplay because you signed up to hear from me, the writer Jasper Nighthawk. You can always unsubscribe.

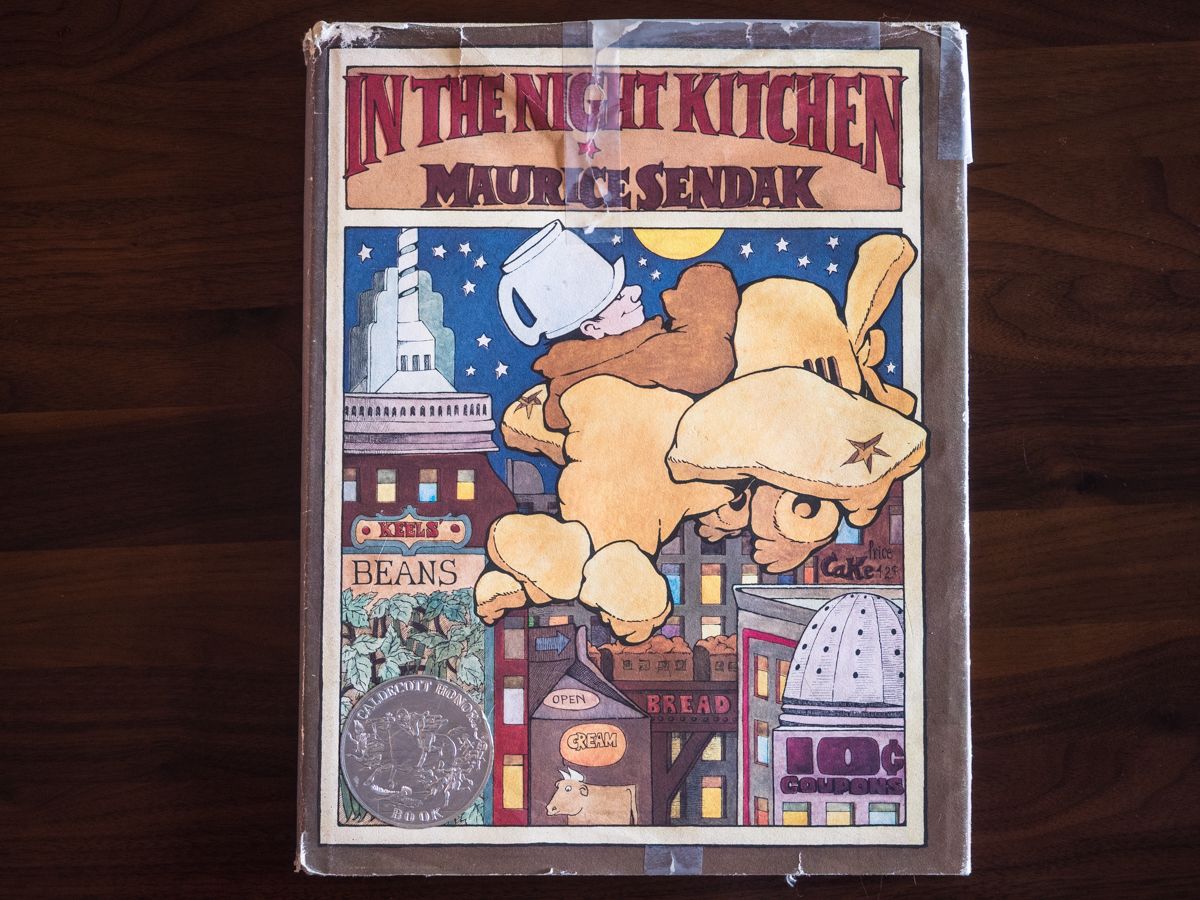

In the Night Kitchen

If you read books aloud to your child every night, it will come to pass that certain, much-revisited books become ingrained, down to their very wording, in both of you, like a shared tattoo.

A few days ago I was making waffles. The kid pointed at the steaming waffle iron and said, “I want to eat right now.” Hardly thinking, I replied, “First we have to wait for the steaming and the making and the smelling and the baking.” The kid got a serious look on his face and ran out of the room. A minute later he returned holding Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen. He glowed with triumph. As the waffles finished cooking, he sat in his mom’s lap, and together they found the page with that line.

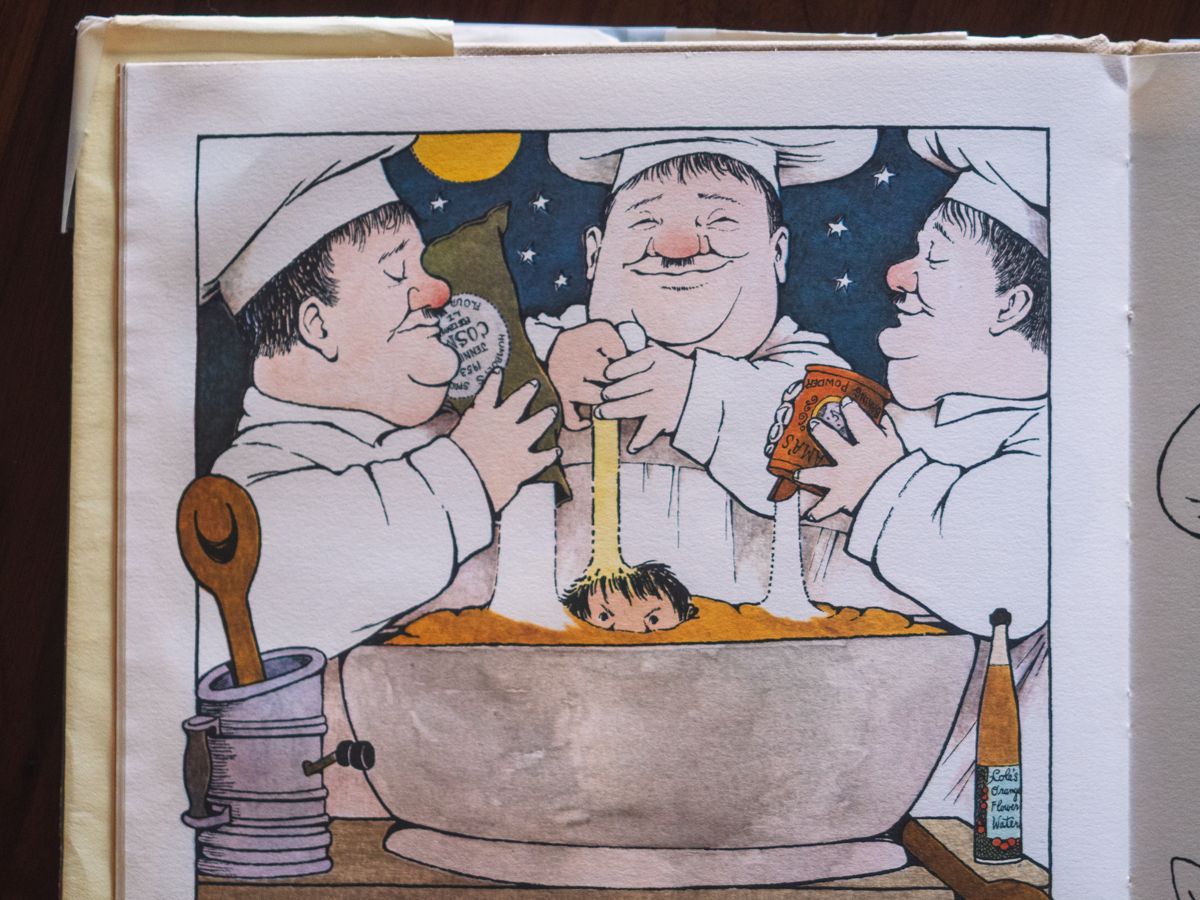

In the Night Kitchen tells the story of a boy named Mickey, who after hearing a racket in the night (“THUMP,” “DUMP CLUMP LUMP,” “BUMP”) yells “QUIET DOWN THERE!” and promptly falls out of his clothes and into the phantasmagoria that is the “night kitchen.” The story advances with the logic of a dream. Three identical bakers mistake him for milk, mix him into their batter, and put him in the “Mickey Oven” to bake “a delicious Mickey-cake.” Mickey escapes the oven and jumps into some bread dough, which he kneads and punches and pounds and pulls into the shape of a single-propeller airplane, which he proceeds to pilot to the top of a giant milk bottle. He dives into the milk and, returning to the surface, pours some down into the batter for the three identical bakers, so they can bake their cake. He then cries “Cock-a-Doodle Doo!” and slides back into bed. The book ends with an insane statement: “And that’s why, thanks to Mickey, we have cake every morning.”

In the Night Kitchen isn’t as famous as another of Sendak’s other masterpieces, Where the Wild Things Are. For my money it’s just as good. The two works echo each other. Both follow a young child on a solitary, nighttime journey to a mythical realm where the child confronts a threat, overcomes the danger through use of their imagination, traverses a body of liquid, and eventually finds their way back to their bedroom.

Put like this, the plot is nothing new. The Prophet Muhammad had his psychedelic night journey to Jerusalem (the Israʾ and Miʿraj); Carl Jung identified an archetype of the “night sea journey” that includes a “complete swallowing up and disappearance of the hero in the belly of the dragon” followed by “slipping out…which happens at the moment of sunrise”; and John Barth lightly satirized the idea in his short story “Night-Sea Journey,” which narrates the experience of a melodramatic sperm. A recent Lightplay even celebrated the wordless children’s book The Night Riders, which illustrates a late-night journey that reaches its moment of maximum tension during an underwater encounter with a giant albino crab and ends with the sunrise.

Still, Sendak’s work, especially in In the Night Kitchen, is something all its own. Despite being pitched towards toddlers, the hero Mickey gets mixed into bread dough and put into a hot oven. It has all the peril and possibility of a dream.

And: what’s up with the three, identical bakers?

On the page that faces this image, Mickey is entirely submerged, except for his plaintive hand, sticking out from the doughy mass. My kid always points at the hand and says, “Oh no!”

The copy of In the Night Kitchen that I read to my kid is the same one that my mom used to read to me, back in the ’90s. The cover is all taped up, and most of the interior pages are warped and dented and creased. Still, the printers did a strikingly beautiful job with this book. The paper is heavy and uncoated; it feels great in the hand and catches the light just so. The black line work and lettering is deep and inky, while the coloring is gentle, muted, earthy. They don’t make ’em like this any more. (1)

Sendak published In the Night Kitchen in 1970—seven years after Where the Wild Things Are. It’s looser and more comic-book-y than that work, with lots of multi-panel spreads and beautiful lettering by Diana Blair.

I love what Sendak said about In the Night Kitchen:

It was an homage to everything I loved: New York, immigrants, Jews, Laurel and Hardy, Mickey Mouse, King Kong, movies. I just jammed them into one cuckoo book.

I do want to talk about the matter of Mickey’s nudity. He is naked for almost the entire book, though of course he spends a lot of the story encased in bread dough. His penis—just an outline—is visible in only four panels. Still, this nudity has led to the work being excluded from libraries across the U.S. It was #21 on the American Library Association’s list of most-challenged books for the years 1990-1999, and it was #24 on the 2000-2009 list, though it didn’t even make the 2010-2019 list. Our culture has strict codes of modesty as well as an unformed terror of pedophilia that can fixate on something like Mickey’s nudity in lieu of actually protecting children. (The book is not pornographic.)

For myself, I recall that when I was a kid and read the book again and again, I loved the fact of Mickey’s un-self-conscious, unremarked-upon nudity. I myself loved being naked. Being raised by hippies out in the woods, I had plenty of opportunities to run around in an Edenic state. But this was the only book in my library that had a naked protagonist. And if you’re going to imagine being baked into an enormous cake or diving into a giant bottle of milk, well, clothes are just going to get in the way. The nudity is necessary.

Sometimes when I finish reading the kid a book, he immediately demands that I read it to him again. And we return to the same ones, night after night. His favorite books we will sometimes read more that twenty times in a single month. It could be annoying, I guess. I remember a conversation with some work colleagues where one of them talked about coming to hate Where the Wild Things Are and developing a technique of skipping pages that helped them breeze through it until their kids got old enough to catch them pulling this trick. I think they were halfway joking. I also think the old saying is true, there’s no accounting for taste. Yet I can’t help but also think that they were doing it wrong.

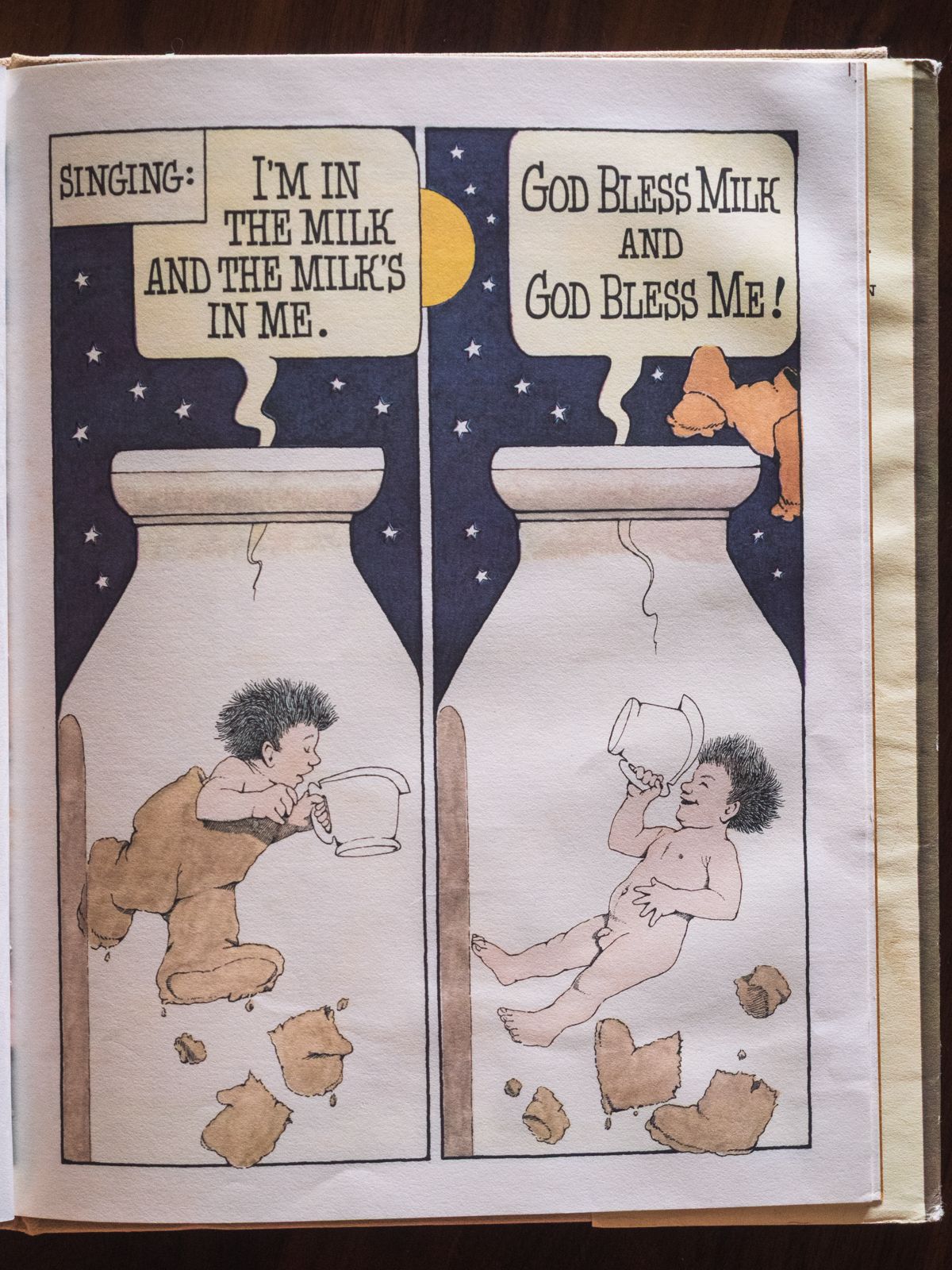

One of the great joys of childrearing is to play or walk or read alongside your kid and thereby to confront the world as you would if you yourself were a one-, two-, three-, or seven-year-old again. The playing requires full immersion, no checking of the phone. The walking can be slow, but you see a thousand details you would walk right by in your adult routine. And if the book is good, you get to sink into its pleasures again and again and again. Once the novelty wears off, you’re left with the artwork itself: the steaming and the making and the smelling and the baking. You are, once again, in the night kitchen. And you’re singing: “I’m in the milk and the milk’s in me. God Bless Milk and God Bless Me!”

NOTES

(1) Nonetheless, the kid’s sections in today’s bookstores do contain many marvels. The other day I bought the kid a book about dump trucks, and the book is not only made in the shape of a dump truck’s silhouette, it has functional wheels attached and can roll around. We have a book printed on some material like Tyvek that was marketed as “impossible to tear.” Indeed, it has never torn. Instead it has warped into a crumpled mess. Another book for some reason has a thick, puffy cover. And I recently saw a waterproof book that is meant to be taken into the bath. Nonetheless, I basically never encounter so nicely-printed a book as In the Night Kitchen, with such luxurious attention to texture and format and the interplay between the two.

I enjoyed Benn Jordan’s latest video, about creating “adversarial” music designed to trip up AI training models and degrade their outputs. He’s developed a technique of adding inaudible-to-human-ears sounds that confuse the algorithms. If our government won’t protect artists, maybe artists need to get aggressive in trying to outwit these AI capitalists who think it’s okay to steal our work as “training data” without permission or compensation.

(I love that this YouTube channel, which I started watching mostly for the synth reviews, has become a locus of anti-Spotify agitation and now anti-AI creativity.)

Also taking an adversarial stance against generative AI? Robin Sloan’s latest zine.

Back to music: why can’t the various streaming platforms (Spotify, Apple Music, etc.) show liner notes? I’ve written in the past about how the streamers push you away from deep connection with the music. But after getting a record player a year ago and returning to vinyl, a further loss has come into focus for me: many (most?) albums throughout history have included not just lyrics and personnel credits but also essays, letters, art, photos, and other notes to the listener. These are such cool ways for artists to add extra layers beyond the recordings that make up the album. But the digital age, and now the age of streaming, have meant, poof, all of that is just gone. WTF?

(I’m currently on a deep dive into the music and world of Alice Coltrane; both she and John Coltrane made extensive, creative use of liner notes; these are strangely hard to access.)

We recently visited family in Chicago. Flying out, we had a clear view of the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System in the Mohave Desert.

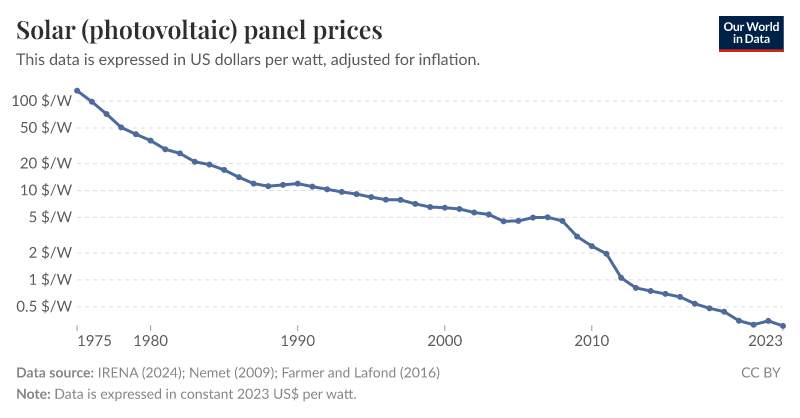

It’s made up of the three glowing pillars out in the desert. They’re very much relics from a lost civilization. Hardly a decade old, the three towers and the 347,000 mirrors that make their water boil will close next year. They were built in a very different economic moment, when solar panels were exponentially more expensive than they are today.

It was nice to be back in Oak Park, Illinois. That town is never not looking like a frame from a Chris Ware comic. (He’s a local.)

The other day, taking a bath, I perched my laptop on the toilet seat and watched “The Hand,” an 18-minute stop-motion animated film about a sculptor being menaced by a white-gloved hand. I highly recommend watching it—it’s available for free on YouTube—and also reading the Animation Obsessive essay that discusses not just the film but also its director Jiří Trnka, the conditions of both its creation (in communist Czechoslovakia), and the general reception it received when it was released (as a one-dimensional Cold War parable).

I love this New York Times article about History for Hire, a prop house in North Hollywood that is at risk of closing because of rising rent and a decline in LA-based film and TV production since the pandemic and the writers’ strike. I especially liked this mention of a special library built around the demands of recreating objects from the past:

Perhaps the most fulfilling part of the job, Pam said, is diving into the history itself. There is an entire library in the warehouse devoted to that work, filled with books and reference guides that could be props themselves.

This must have been a dreamy assignment for the photographer (Jake Michaels) who worked on this story.

I hope that the scrawler of this graffiti, on a forlorn strip under the L, has found their way to a better place.

My partner and her sister spent much of our trip to Chicago processing many, many boxes of childhood and family ephemera. Among the treasures found was this type specimen created many moons ago by my sister-in-law Julia. Spice!

Why not buy a couple mangos, wait for them to ripen, then peel and cut them up? Eat them out of a bowl with a fork, or put them on top of your toasted oatmeal. You deserve some fruity sweetness.

I’m so glad to have you as a reader. If you’ve enjoyed this email, have you considered forwarding it to a friend?